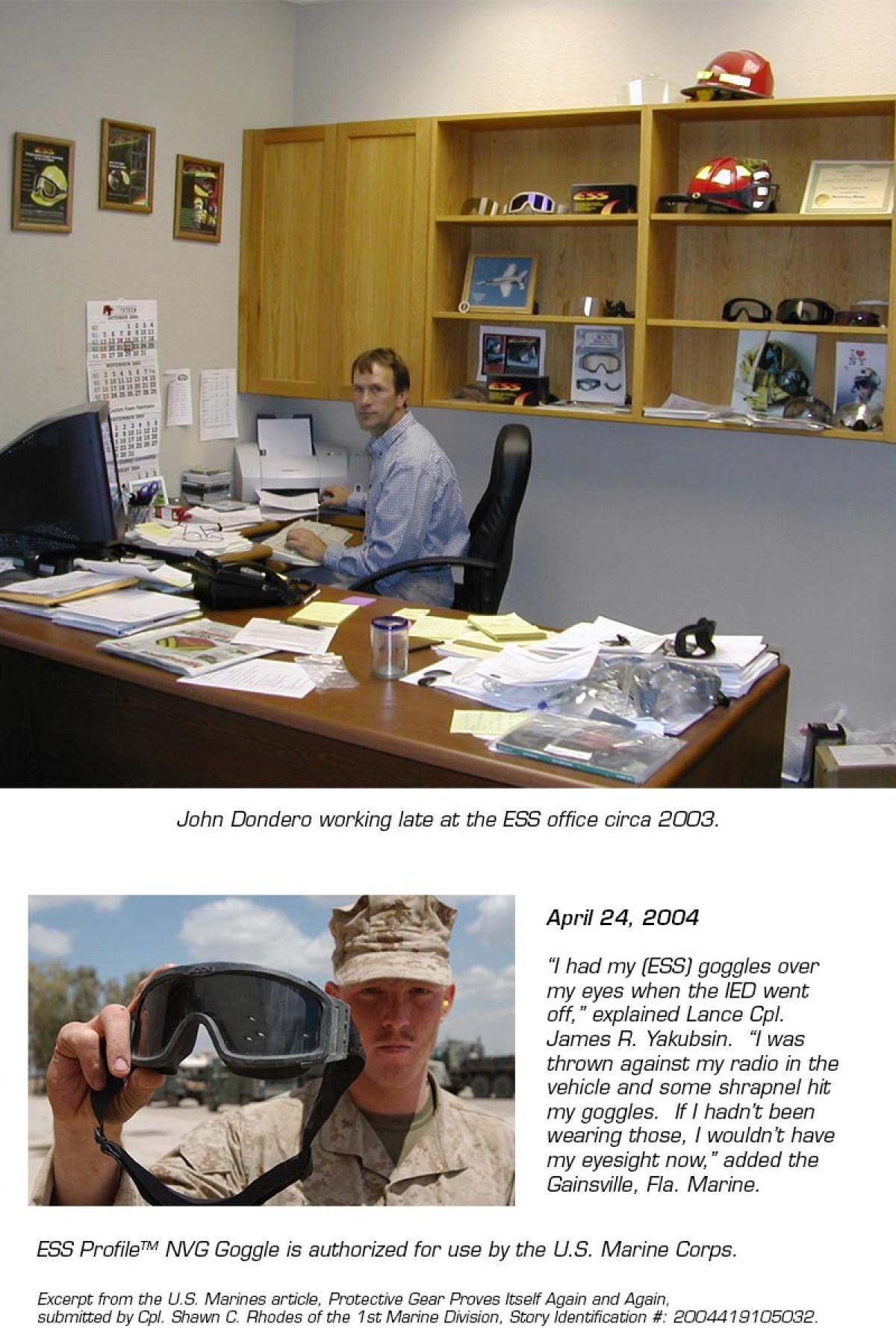

JOHN DONDERO

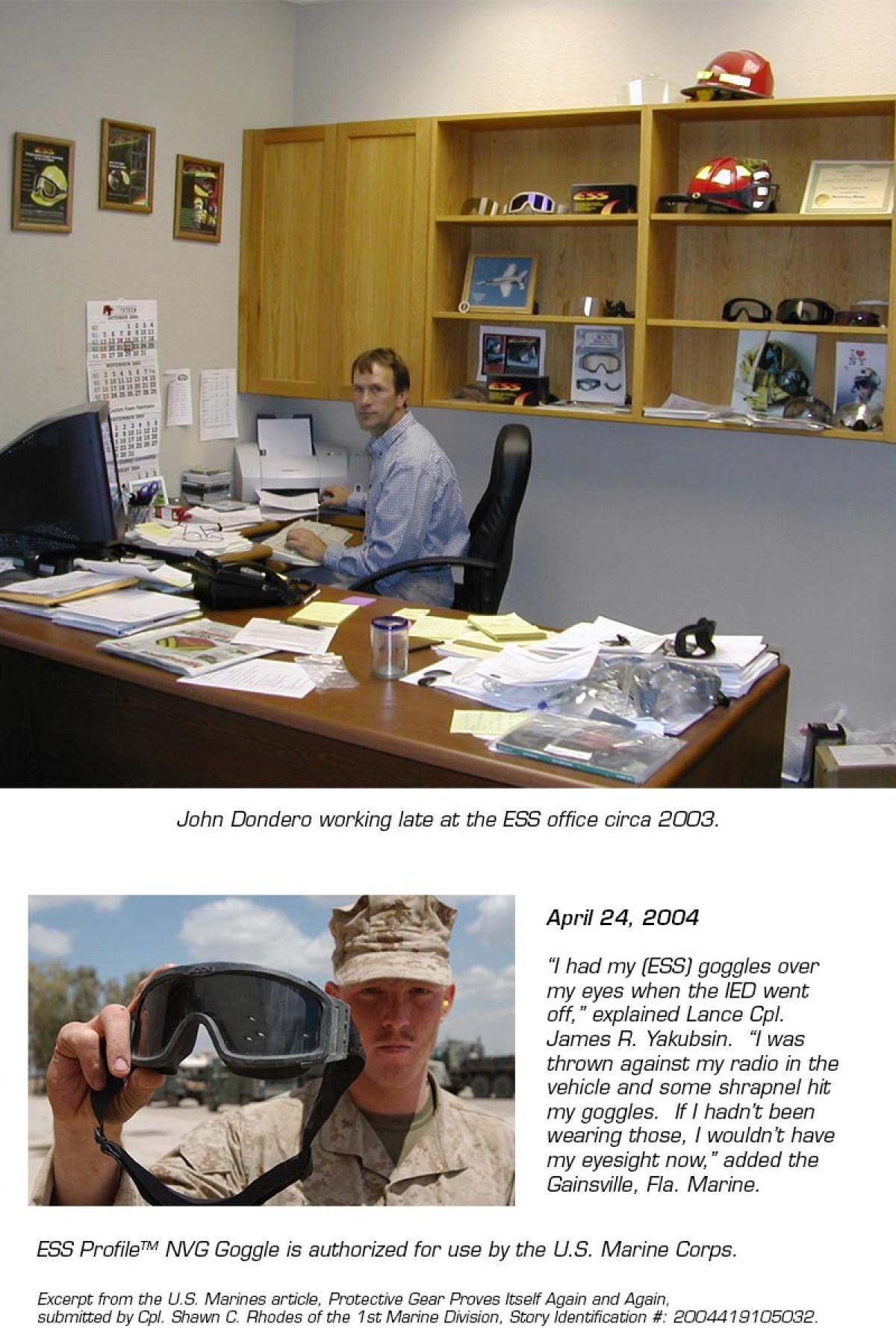

To celebrate the 25th Anniversary of ESS, we were able to catch up with retired ESS founder, John Dondero. The ESS team joined General Manager Mike Vigueria as he interviewed John about how the company was started, the breakthroughs, and the incredible product innovations that can occur through intense listening to our customers. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Interview with ESS founder, John Dondero

Mike Vigueria: We're celebrating our 25th year of eye protection. ESS culture started with you, John. And we've continued that legacy. It's an honor to sit down with you today.

John Dondero: Thank you.

Mike Vigueria: We are interested in how ESS got started as a company. What is your background? What were you doing for work prior to founding the company?

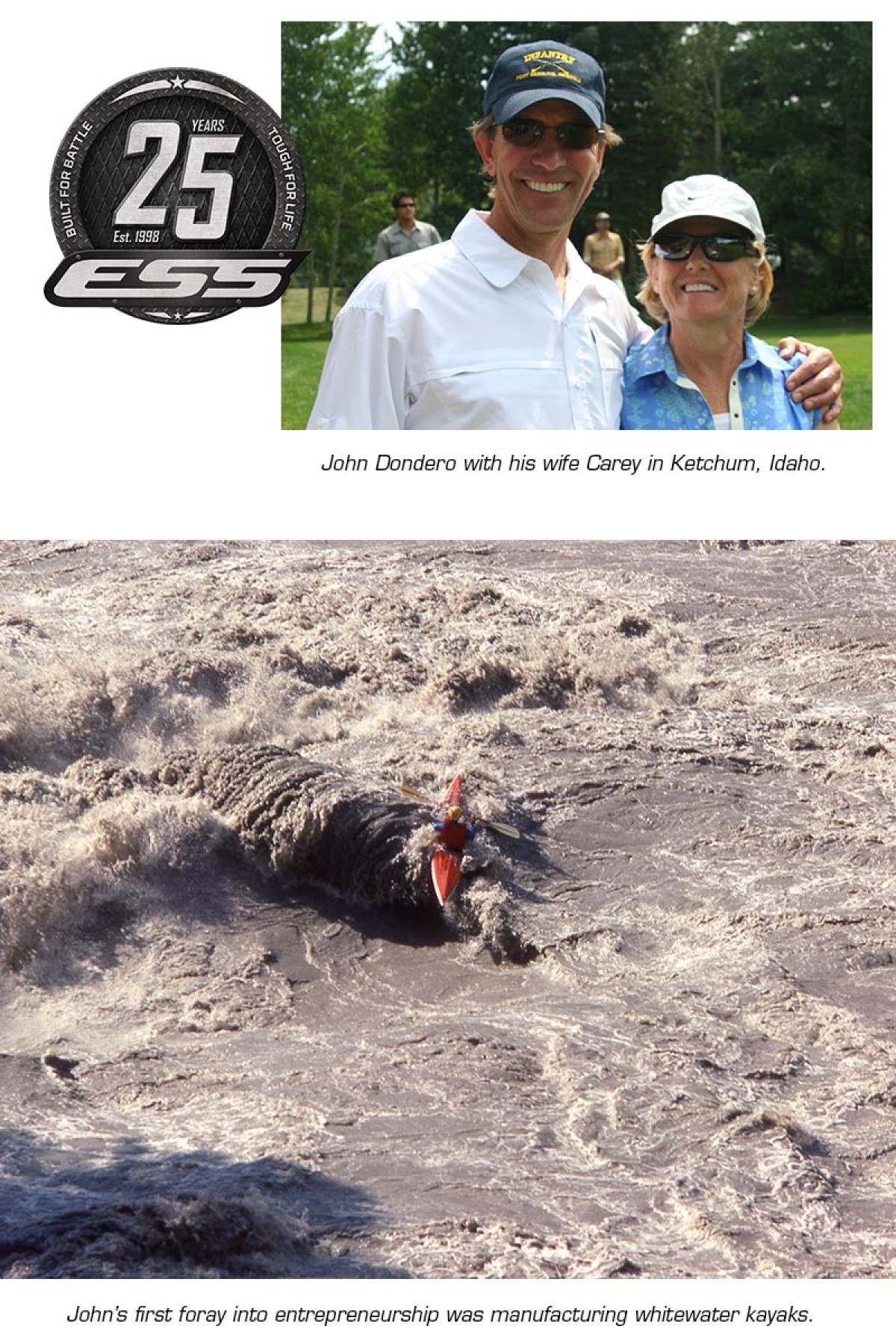

John Dondero: My work history aligned well with the formation of ESS and its success. I spent my early 20s in the resort town of Ketchum, Idaho and I was always really active. My first foray into entrepreneurship was in the manufacturing business of whitewater kayaks. I put together a company in Ketchum where we were making fiberglass kayaks and selling them primarily around the West. It taught me so much about plastics, industry materials, and just some of the basics of how things are made and what is available. It was really a great start. I always had an entrepreneurial inclination.

During that time, I was also a ski patrolman and a river guide. A group of us started Sun Valley Helicopter Ski Guides, but I got out of that fairly quickly because I was offered a job at Scott USA. They made a lot of different products, ski boots, ski poles, and ski and motocross goggles. I went to work as the Goggle Product Engineer. Soon, I was also in charge of the R&D shop. That was a really important turning point in my career because while I had a significant background in plastics, this drew me into eyewear products and gave me an understanding what makes a good goggle or what makes a good piece of eyewear.

That work experience was really the baseline for ESS and our ability to excel in the competitive markets of the military and firefighting.

Mike Vigueria: What was your next step?

John Dondero: Scott USA was sold and they moved their headquarters. I went to work for a company based in San Diego, California by the name of JT Racing which was one of the premier motocross gear providers. I continued to live in Ketchum and worked and developed products at JT for 18 years. Part of the reason I stayed with the company so long was that we had a growing family and I knew if I started my own business I would be pulled away from my family. I thought it was really important to work for someone else at that time.

And I really enjoyed it. It was fascinating. I went all over the world in different fashions with JT and we developed some great products. Eventually, the motocross product line, that included goggles and glasses, was transitioned to paintball, which was an up-and-coming sport but there were no standards in the paintball industry. I personally got very involved in ASTM, which is a standards organization [American Society for Testing and Materials] that eventually created a standard specific for paintball eye protection. It was another interesting stepping stone because within the eyewear committees, I met not only individuals in the fire market but also individuals in the military who were part of the ASTM committee. That ASTM involvement was really significant as are many of these points along the way.

Mike Vigueria: What pushed you to go out on your own?

John Dondero: On January 1st, 1998, I decided it was now or never. I had always wanted to have my own company. My wife and I had discussed it many times and I realized that if we didn't do it now, we were never going to do it. And so with two kids in college, and one in high school as a senior, I wrote my letter of resignation and started ESS on January 1st. It was risky. It was daunting. But I knew that there was enough opportunity out there that I would make it work.

The primary focus for ESS initially — the opportunity that was most glaring — was a change that had occurred in the fire safety standards. The structural firefighting standards required a face shield, originally. And that wasn't even considered primary eye protection by their standards because it did not provide enough protection. There could be debris that might fly up underneath the shield and injure firefighters. But the goggles were eventually allowed as primary eye protection if they met the standards. So, with that opportunity, I thought this would be a great product line to create a firefighting goggle that would work for structural firefighting and, with some modifications, for wildland firefighting.

So, we went about putting together the company and created a business plan. I got a few investors, formed the company and designed a product. We made all the molds — the tooling — those of you familiar with the product development timelines know how long that takes. Once we set up the manufacturing, we then had to go through all the testing and certification with the goggles. We established one patent initially, and believe it or not, from the company’s start on January 1st, we sold our first product in September of that year. Just nine months later.

Mike Vigueria: That's impressive.

John Dondero: Wildland firefighting was the first target. Second to that goggle, was creating a Structural firefighting goggle. Meeting the Structural standards were a little bit challenging. There was a test that required the goggle to be placed on a helmet and put in an oven at 500 degrees Fahrenheit. And when the oven returned to temperature at 500 degrees, the google had to last five minutes on top of the helmet and not droop below the brim of the helmet. Most of the materials that are now used in sports eyewear would be a pool on the bottom of the oven floor. So it took a long time to figure out what unique, specific materials would withstand that kind of environment and perform well. From the strap to the frame material, that was a challenge.

Mike Vigueria: That is still the standard that we have to meet.

John Dondero: And it was through much research and digging that I found a material which actually gave us that unique edge and was able to meet the high-temperature requirements, but it took a while. Always in the back of my mind was the military — and especially because of the associations that I had had with those individuals both in the Army and in the Navy while I was on the Standards Committees.

When I was at JT, we bid on a production contract for the Sun, Wind, and Dust (SWD) Goggles — the old military goggle. The government would put out these contracts for open market bids. It was a MIL standard that you had to meet. The materials were specified, and one could use their molds and basically assemble the goggles and supply them to the military. I put together a bid and we lost on a technicality. I was kind of pissed off that we lost and I really wanted to go after that goggle. It was a terrible goggle. And it always bugged me that military personnel had to wear that as their eye protection.

It's a goggle that was developed in 1943. It does not have any ventilation and it fits poorly. They changed it slightly when they put a ballistic lens in it, but that only made the fit worse. In fact, as I pointed out to the eyewear specialist in charge of Army eyewear, that goggle doesn't even meet OSHA requirements. You can't legally wear that on a construction job site. And he looked at me with big eyes — he was a little dumbfounded because if that were ever disclosed it wouldn't be good. I told him it fails the flammability test — the strap catches fire and continues to burn faster than allowed. Anyway, that definitely got their attention. And I think it gained us a little respect because they understood that we knew eyewear and that we were really focused on getting it right.

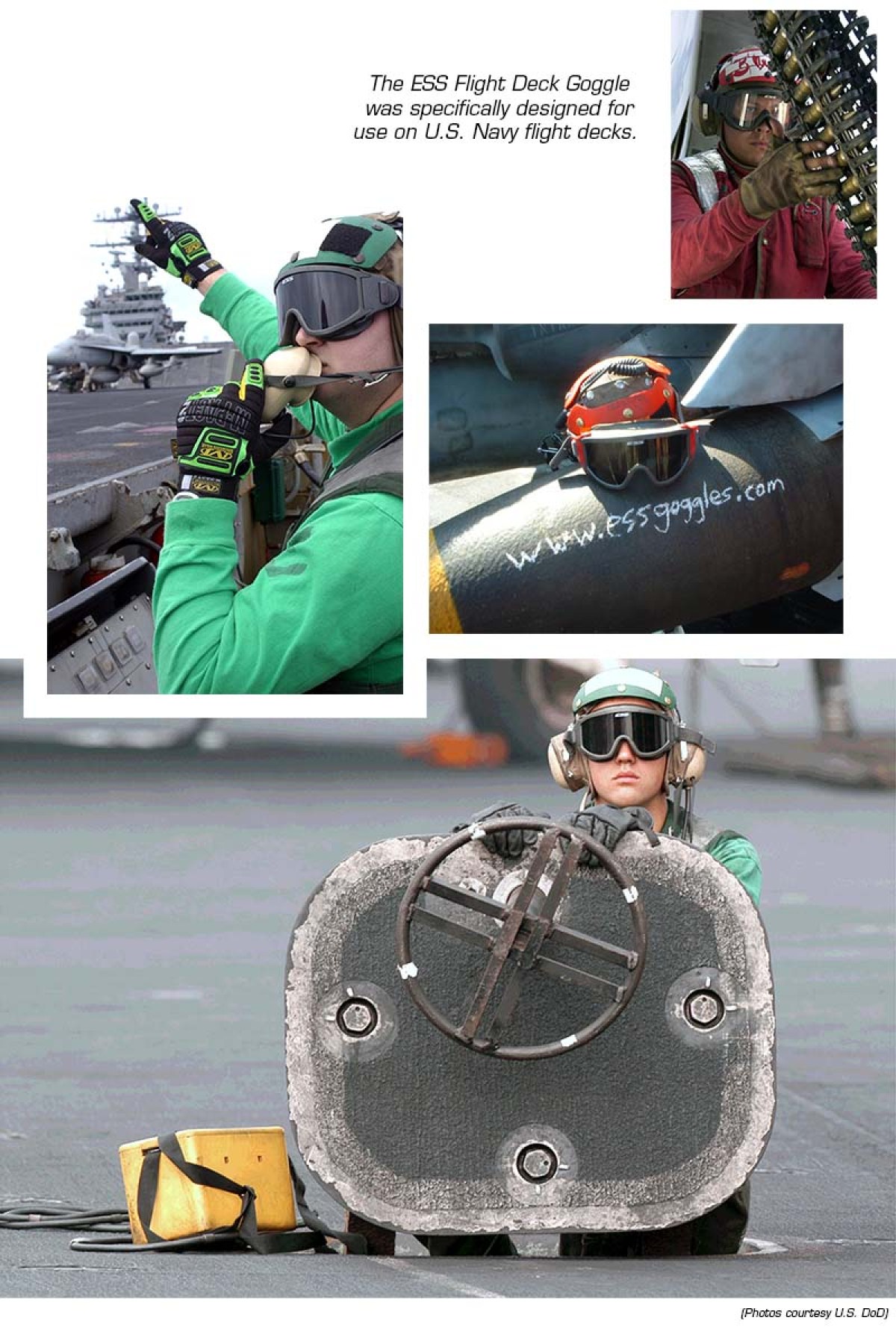

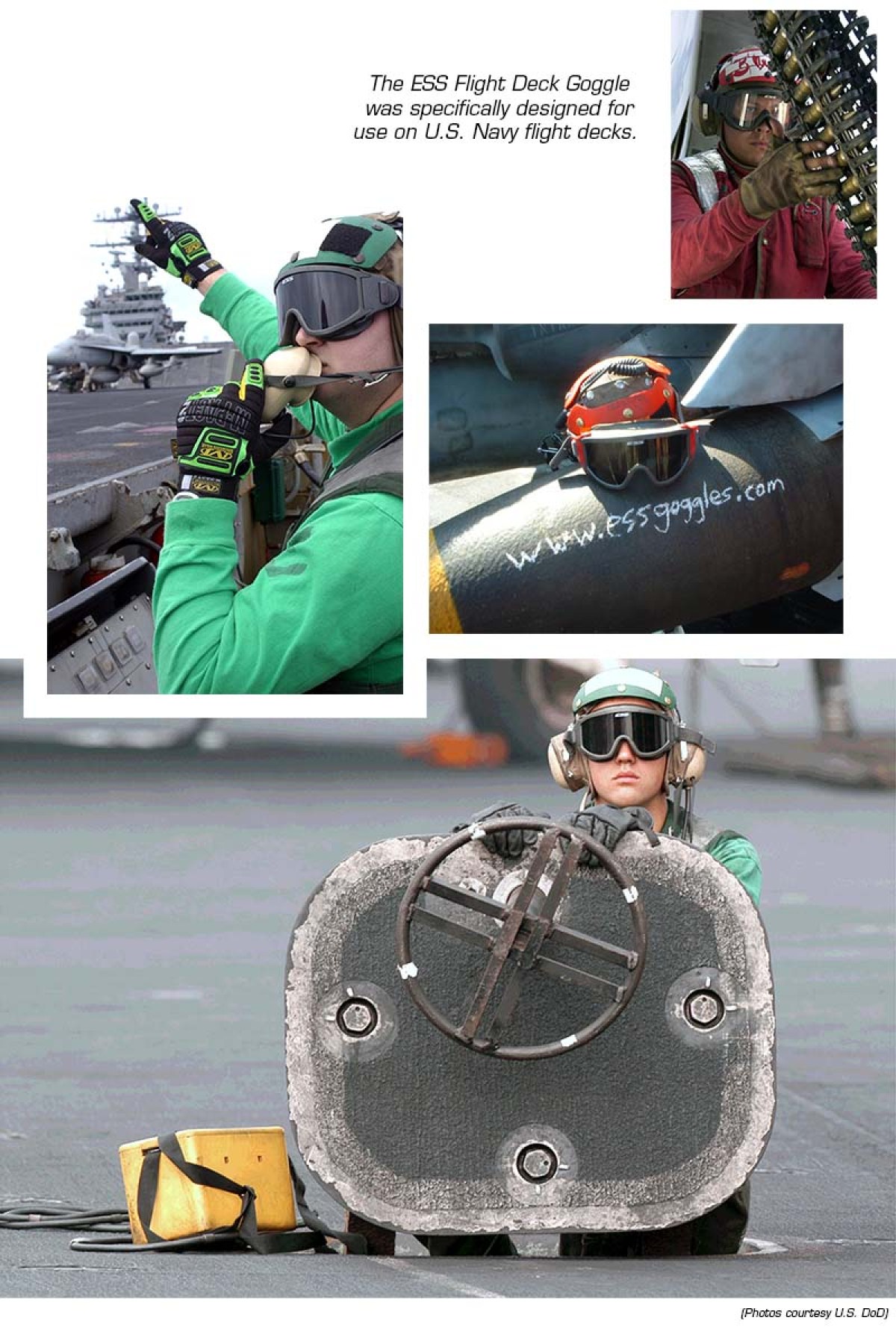

The military was always a target of mine. It turned out that a friend who was an avid powder skier was also a captain in the Navy. He understood how eyewear should work, he knew that a goggle should have ventilation, and he knew it should have an anti-fog on the inside of the lens. When I gave him our test reports, he took 20 goggles and put them on the flight deck. Now, you're not supposed to do that because it wasn't an authorized product. But he trusted us and he knew that we had a better goggle than the goggle those poor guys on the flight deck had to wear for hours on end. And they loved them. The sailors loved them. They came back and wanted to buy some more.

Well, we didn't have an NSN [National Stock Number]. That number drove the whole system and they gave us one really quickly. So that was our first success. And then I turned our focus back to the Army. I told them “the Navy's getting ahead of you, they've already issued an NSN for our goggle”. I think that motivated some of the decision makers in the Army to look carefully at what we had to offer.

About that time, Operation Enduring Freedom came around. There was a famous meeting with a sergeant major who was not on our payroll but who was convinced that we had the best product out there. There was a series of goggles and eyewear of various sorts laid out on the table. The general came by and asked the sergeant major which one would you recommend?

[John tears up. Pauses.]

I don't know where that emotion came from.

Mike Vigueria: Well, John... That was the beginning of such huge success. It transformed your life into something maybe you couldn't even imagine at that time.

John Dondero: It was very cool. And so with that, we engaged the Army's procurement system. The head of procurement said something like, "You know, we like your product. And it's gotten great reviews in the field. And clearly, it meets the standards. But you're a small company. Can you really meet our needs?" And I was in a great position to explain that our goggles were manufactured in the largest goggle manufacturing facility in the world. Of course, we can meet your needs!

Mike Vigueria: That was huge for the company.

John Dondero: That was the real shot in the arm that got us going. We had been selling pretty well to the fire market, although that's a much smaller market. We were doing really well with the Navy. We had a flight deck goggle specifically designed for the Navy flight deck. We had several models for the Army. We were branching out and going to some of the international trade shows, and with the success in the US military, it just led to success elsewhere because all those other countries would look at what the U.S. was doing. It wasn't that many years before we were selling to over 100 countries around the world, which is pretty damn impressive for a little company in the mountains of Idaho.

Mike Vigueria: At that point, John, how many people would you say were working for ESS?

John Dondero: With all the manufacturing, purchasing, and most of the testing done at Smith, I think we probably only had under 15 employees at that time, not many, but very focused and determined to do the right thing.

Mike Vigueria: And it hadn’t been that long from going from a two-man shop. Haven’t I heard a story about a couple of guys waiting for the fax machine to ring with an order?

John Dondero: Those were the early days. We shared an office with a realtor and a friend who was a fisherman and investor, and we all shared this fax machine. When that machine would ring, we'd race over to it hoping it was an order.

Another interesting story is the decision to go forward with a newly developed goggle — the Profile NVG. The Army needed something other than the Sun, Wind, and Dust goggle and an engineer in the Army told me they had a contract out for the development of a new goggle. For a bunch of reasons, I knew it was not going to be successful. And sure enough, after several years of trying, and more than a million dollars spent, their new development project failed. Anticipating this, we had fast-tracked the development of the NVG. We had it tested and presented it, about the same time the Army’s development project was rejected. Our new goggle, the NVG, was a big success, it made a huge difference to the guys wearing it in the field. So, it worked well to make big decisions by putting all the little pieces together from my background dealing with the various individuals and entities. Listening to the users and understanding their needs is so important.

Mike Vigueria: With the 25th year anniversary, we are bringing back the slogan, "The end result of intense listening."

John Dondero: That's lovely. That’s always been at the core of our business. We were constantly working on improving on designs and listening to what our customers need.

Mike Vigueria: Can you talk more about listening to the customers' needs? Going from a concept in your brain to it going out the door?

John Dondero: It's a matter of putting the most important pieces together and prioritizing them. In the case of the NVG, the Army gave us a problem to solve. We needed to create a solution. So one of the first things I did was determine the offset of the lens from the eyes in order to work under the night vision systems. So that becomes the baseline. You've got to have just that offset or less in order for the goggle to work. That establishes the lens offset, and from there you integrate it with the face fit. Then you work in between the two.

Along the way we developed a quick strap adjustment system, that patented system for the speed strap. It's just a matter of understanding what the critical design elements are and what works in the field. In that case, it was how far is the lens off the face? Then, face fit is critical. and you design in the maximum amount of ventilation. You can always control the flow-through by using different filter materials. But you must have the holes to maximize ventilation if you need it.

That brought us to a place where we were in a position to really kick it in gear and get into the development of products like the Crossbow and fine-tuning some of the other products. We did the Advancer V-12. That was a goggle that had more cool ideas but really didn't get very far except for the British contract. But I was always proud of that one because it was a design that addressed extreme fogging conditions by moving the lens away from the frame and getting a free flow of air behind the lens - that is the ultimate way of defogging, aside from a fan, which we also had — the fan goggle. But the fan goggle just wasn't really well-received by the military.

Mike Vigueria: Obviously we use that AVS (Adjustable Ventilation System) patent that you got for the Advancer V-12 in our new Influx goggles. It’s an interesting progression because the original Flight Deck goggle has now morphed into the AirBoss goggle which is based on the Influx AVS platform. It’s a much better-performing goggle.

John Dondero: So, the genesis of the AVS idea was interesting. I was riding dirt bikes in the early spring and it turned into a snowstorm. I could not get my goggles to stop fogging. It was cold up here in the mountains. I'd stop and my goggles would fog, and I’d pull them off my face and I thought, "There's got to be a way where I can just advance these." Back in my shop, I created these helmet attachment systems that allowed you to click and pull the goggles off your face and kind of float them just far enough off where you get airflow and the goggles would de-fog immediately. Recognizing that, when I was out freezing my fingers off in the snowy mountains of Idaho, I eventually conceived of that advancing lens system with a stationary base on your face — but the lens itself would just snap forward, provide that open airspace and give you the air free flow that was needed. That was the genesis of the Advancer.

Mike Vigueria: Tell us about the P-2B Rx system that you created. As I understand, it was a perfect example of how we heard the need and rapidly developed a product to meet the need and that really launched us ahead of our competitors.

John Dondero: Those are the kinds of challenges that I love. But that was a tough one. During development, we’d think we had just the right Rx hanger design and we’d set-up and make the molds. You have to go through all the steps to get a sample product that's really representative. And then when you shoot it in the lab’s high velocity impact test, it dislodges. We wondered how are we going to keep it in place, and meet the test? In addition, we needed to provide the right lens offsets — the ocular distance from the eye in order to have the right optics in the finished product? But yeah, that was a scramble, and I was really proud of the R&D team. They did a wonderful job figuring out how we were going to fit the Rx into the goggle and make it work. In fact, our carrier had to work in both the military goggle as well as our eyeshield. It was definitely a triumph.

Mike Vigueria: It's a good time to transition to the culture of ESS. You spent a lot of years building out a culture. It was a family. I remember, even when I was hired, and as we hired others afterward, we put more emphasis on a good fit and somebody who would be part of the team and believe in ESS, than we would on their past and their history and their education. At least that was my perception. I'd like to hear a little bit about that. How did you build the team that we had? And what was your mindset there? What's your philosophy behind being an entrepreneur, and transitioning into a very large company?

John Dondero: We were fortunate living in this community. Per capita, there's an incredible amount of talented individuals. And many of them were young. They really were anxious to sink their teeth into something meaningful. It was a fun company. There was no question that we were focused and we were serious about being successful. Initially, we paid our employees pretty minimal wages, but if we were successful at the end of the year, we bonused everybody, which allowed us to keep the company going.

And it created a spirit of camaraderie, of wanting success. It was just a real scrappy attitude, "We can do it, let's show the big guys that we can be successful and that we know what we're doing." That was the culture that permeated through everybody. It was really a close-knit group of individuals who were proud of the products we were providing. What could be more rewarding than to meet the needs and protect the eyes of first responders, firefighters, and military personnel? It doesn't get better than that.

Mike Vigueria: Were there things as a young man that drove you in this direction?

John Dondero: During World War II, my dad was a wood pattern maker. We always had a shop in our house and I was always tinkering in the shop making stuff, whether it be with a lathe, a drill press, a hand plane, or whatever. It was always hands-on and with an interest in how things work. I would take things apart and ruin movie cameras and such because I couldn't put them back together. But at least I saw what they look like inside. I'm just wired that way, just trying to figure out better ways to build a better mousetrap basically and what makes things work, I'm always fascinated by that.

One of the objectives in a thermal lens is to create a warm inner lens. And as a couple of us were looking at a thin sheet of Lexan that had gold plating on it, I took it and curved it around my face and felt the radiant heat from my face being reflected back from the gold-plated lens. We thought it was a great way to heat an inner lens — put the reflective gold-plated lens facing inward and it would automatically heat up the inner lens from your body’s radiant heat. So, we put together a thermal lens with that gold sheen facing inward and I went skiing with the goggle. Unfortunately, although gold-plating had excellent thermal reflectivity and warmed the inner lens, all I could see was my eyeball! It was like a mirror and you couldn’t see much through the lens.

There's still an opportunity, perhaps with some kind of anti-reflective coating. But that's just how my mind works when you're trying to figure out what little tricks you can use to overcome the challenges of fogging or ventilation or whatever it is. That's the quirkiness of how an engineering mind works, trying to figure out how to make better products.

Mike Vigueria: And knowing you, John, I think it's fair to say there's an element of not giving up too. You keep tweaking, keep trying, say okay, we're going to shave a little off here, we're going to add some material here until it works. And that always impressed me.

John Dondero: Absolutely, you can't give up and you just have to keep going. You have the confidence that you can do it — that there is a way to do it. Now, it's just a matter of finding out how. And that's what drives you. You never think, “Oh, my God, that can't be done.”

I can't believe it's been 25 years. It just floors me. Absolutely floors me. Time flies. I feel fortunate to have started something that has lasted so long and gives back to its users. Keep up the good work of listening and protecting people’s eyesight.

***

We are giving away a pair of Special Edition Silver 5B & Rollbar Sunglasses. These kits include; a 25th Anniversary Sunglass, a commemorative 25th Anniversary Challenge Coin, microfiber pouch, and Silver Foil sticker. Promotion ends March 30, 2023.